Fathers of children with autism share the ups and downs of raising a special child.

|

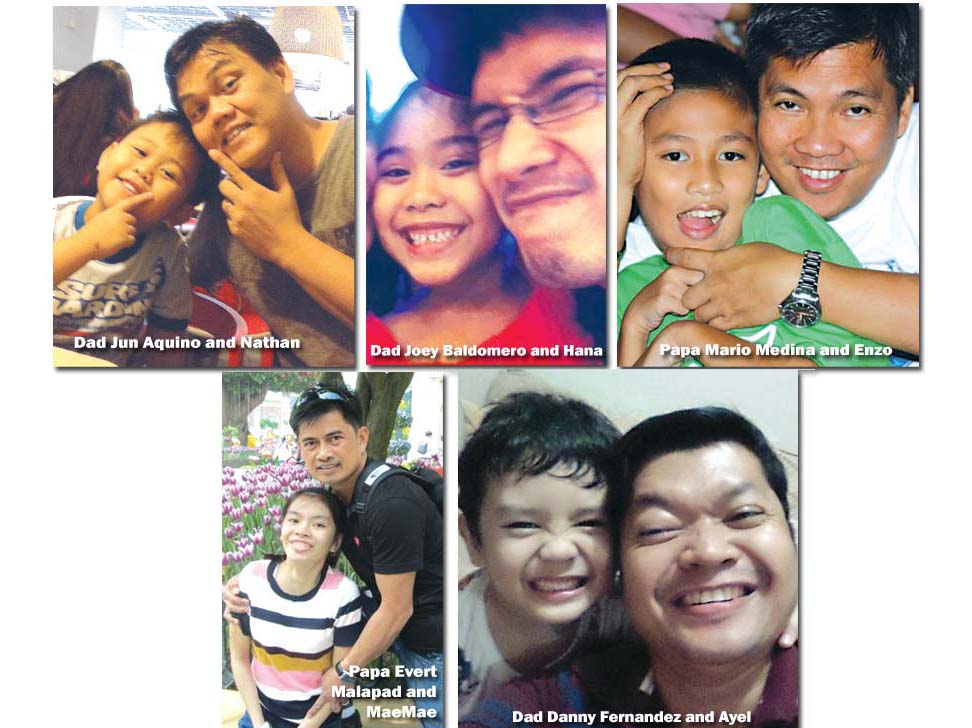

| Dads with children with autism |

When it comes to raising special children, it is often the mothers who work closely with their kids. they are the ones who take them to their developmental pediatricians, their therapists, and the ones who take them to and from school.

But as times have changed, so have the roles of fathers in raising their special children. None of this was more evident than at the June family support group meeting of the Autism Society Philippines (ASP). Held at the Starlight Training School for Special Youth in Imus, Cavite, the group featured three fathers who have put in more than their fair share of work in caring for their special child.

Speaking at the support group were retired career Ambassador Alfredo L. Almendrala, former ASP trustee and lifetime member Evert L. Malapad, and Albert Aragon. Almendrala is the father to Mike, a person with autism (PWA) who now holds a permanent position as an administrative assistant in the head office of the Philippine Information Agency. Malapad has a Master’s degree in Education, major in Special Education, and is the father to Mae-Mae, a 17-year-old PWA.

Dang Koe, ASP chair emeritus, says the family support groups (FSG) are an integral part of the ASP, and has been part of the group since ASP’s establishment 25 years ago.

“It started with 11 mothers na nagkita-kita sa doctor’s office. Casual lang sila nagme-meet, palakasan ng loob, and then they thought of putting up the ASP,” she says. “Ang usual na pumupunta sa FSG ay parents of newly diagnosed children or mga hindi na alam kung anong gagawin nila so they ask the more seasoned, experienced parents.”

FSGs are held every third Saturday of the month, and is usually a free-flowing discussion overseen by a moderator who summarizes the discussions at the end of the FSGs. It is usually the first activity held by new ASP chapters all over the country.

FROM DENIAL TO ACCEPTANCE

Aragon, who was the moderator for this FSG centered on the father’s role in raising special children, began the discussion by asking the others how they first reacted to learning that their children had autism. Reactions ranged from denial to immediate acceptance.

Malapad, for instance, insisted on a second opinion before accepting that his daughter was under the autism spectrum.

“Sabi nung asawa ko, may kakaiba siyang napapansin kay Mae-Mae. Dinala namin siya sa St. Luke’s at sinabi na may autism siya. Mabigat dahil wala naman kaming alam doon,” he recalls. “Pero ang plano namin ay magtanong pa sa ibang doctor kasi hindi talaga ako naniwala na si Mae-Mae ay may autism.”

It was different for Almendrala, who despite having his son Mike at a time when an autism diagnosis wasn’t yet widely accepted, immediately admitted that there was something special about his child.

“Nung na-diagnose si Michael, he was already eight years old. ‘Yung panahon ni Mike, wala pa ‘yung autism sa vocabulary ng society. Wala namang masyadong iba sa behavior niya, pero wala siyang speech,” he shares. “Pero hindi ako naniniwala kasi naririnig niya ‘yung TV sa kabilang kuwarto. Labas kaagad ‘yan para tingnan ‘yung TV. Nung na-diagnose siya, tanggap ko kaagad.”

For Malapad, it was a longer journey towards acceptance, but one that would drastically change his life. Before Mae-Mae’s diagnosis, he was working in Saudi Arabia, and had planned to open up a shop on his return. He was hoping that Mae-Mae would become the doctor in the family.

“Mahirap tanggapin, kasi kung ganiyan talaga ‘yung condition niya, wala na ‘yung pangarap ko. Ang plano namin ay maging doctor si Mae-Mae. Sumanga ‘yung buhay ko. Kung gusto kong maging mekaniko dati, ngayon, special education teacher ako,” he reveals. “Hindi naging mahirap sa akin na kumuha ng Education, ng masteral program sa education, at ngayon natuturuan ko na ang ibang mga children at adults with special needs.”

LIFE-CHANGING

Mae-Mae has changed the Malapad family’s life in other ways as well. The change of career has meant a lesser income, and the family has learned to tighten their belts to compensate.

“Talagang tipid lahat. Si Apple (Evert’s wife) lang ang bumibili ng damit kasi siya lang ang may trabaho. Luma ang cellphone. Basta ilaan mo ‘yung natitipid sa check-up at therapy. Talagang kasama sa acceptance na marami kang isasakripisyo. Surviving talaga kami pagdating sa finances,” he says. “Gumagawa ako ng paraan para kumita. Tumutulong ako sa mga kaibigan. Kahit papaano, yung pambili ko ng load o pang-gasolina, nakakakuha dahil meron akong part time na trabaho. Napapag-usapan naman.”

For Almendrala, having Mike brought about a change of temperament. A former soldier, he says that he had a short temper before he was faced with the challenge of raising a child with autism.

“Mas marami ang naitulong niya sa akin kesa ako sa kaniya. Mainit ang ulo ko. Ang unang reaction ko sa kaniya dati ay nagloloko lang siya. Sa ulo ko, hindi siya dapat binebeybi,” he shares. “Pero dahil sa kaniya, lumambot ako at hindi lang sa kaniya kundi pati sa iba kong anak. I learned humility, tolerance, and compassion.”

It is also time for society at large, says Almendrala, to learn the humility, tolerance, and compassion that Mike has taught him.

“I think what we should do is we let society see that this person is this person and that he has as much right to exist in this space as any other person. He should be accepted as he is, and if he should be helped, he should be helped,” he proclaims. “That should be the information that we give them. May kapansanan ang tao at kailangan tulungan. Kailangan imulat ang mata ng mga tao na may segment ng society na ganito at kailangan tulungan.”

This article by Ronald Lim appeared in the print and

on-line version of the Manila Bulletin on 23 June 2014.

Posted in:

Posted in: